We all know that our diet is absolutely critical to our health. But what perhaps a lot of us don’t realise is that our diet can also be absolutely critical to the health of people thousands of kilometres away, who we’ve never met.

That’s because food production can have some nasty by-products, from the greenhouse gases that fuel climate change to air pollutants such as ammonia, which contributes to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) – the stuff that’s small enough to get deep into the lungs and cause permanent damage. So it’s where food is produced that matters – that’s where people suffer from the negative consequences, and it’s often very far away from where most the food is eaten. In other words, our careless food choices risk making less privileged people more sick.

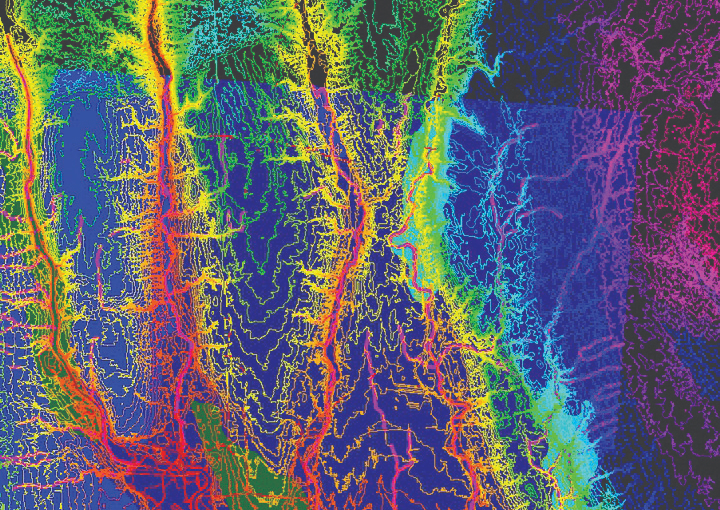

Over the past few decades, mainland China has got rich faster than any other society in human history – and with rapidly growing wealth, inevitably, come profound dietary changes. People eat more, for a start, but they also eat differently – in particular, they consume a lot more meat. As a recent Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) study has shown, that has caused some major challenges in agricultural regions. Food is most intensively consumed in the wealthier areas of the nation, but, with agricultural land frequently in short supply in those wealthier areas, it’s most often produced in less moneyed regions – in mainland China, typically further inland.

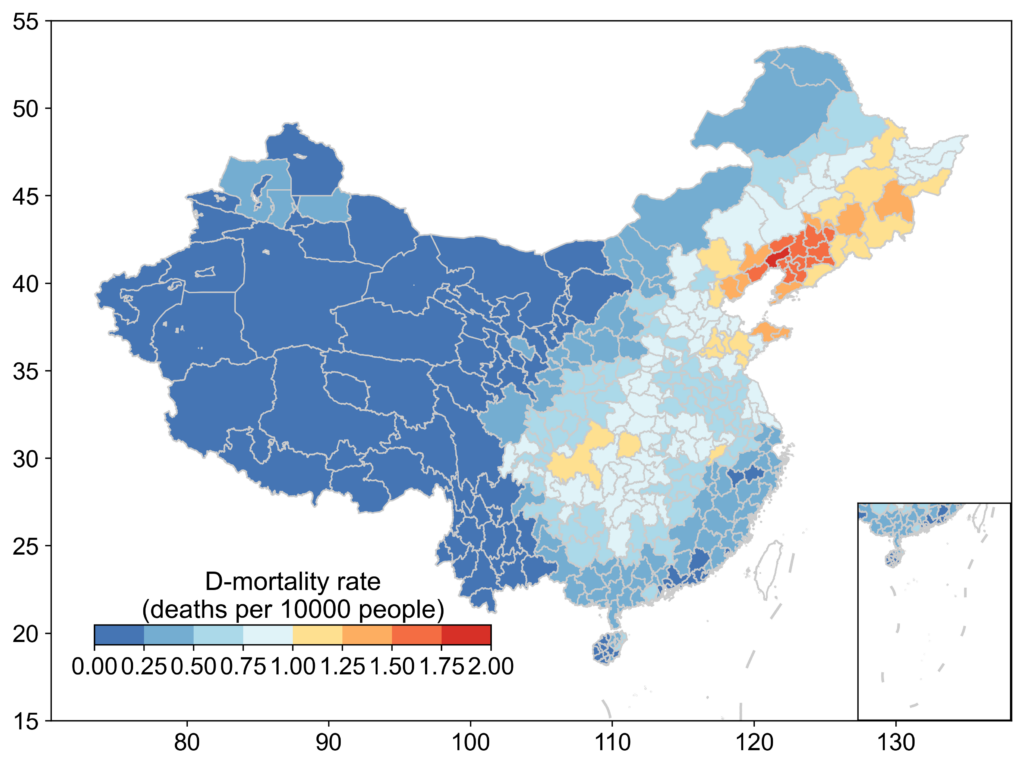

It’s long been pretty obvious that food production, and in particular meat production, is closely tied to environmental pollution. However, no one had previously linked the environmental and social sides of the coin. The CUHK team did this by analysing simulated air quality data both with and without the influence of dietary changes, and combining that with a public health model showing the impact on death rates of different air pollutants, as well as with a spatial statistical model to determine the social factors that contribute to pollution-related deaths. They found that, shockingly, the changes in the nation’s diet have led to an increase in PM2.5-related mortality rates in poorer food-producing regions that are twice as high as those in the richer regions.

The study was triggered by a 2021 study from the same team. “Our research revealed that dietary transitions from plant-based to meat-intensive diets between 1980 and 2010 contributed up to 20% of the rise in particulate matter pollution and the related premature deaths in mainland China,” says Professor Amos Tai Pui-kuen, Associate Professor of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and leader of the recent study. “We noticed that these diet-driven premature deaths were unevenly distributed across the country, with the highest levels in the agricultural regions where the populations are generally poorer.”

Meat production is the most environmentally damaging form of food production, contributing to 54% of ammonia emissions, mostly associated with animal waste in livestock facilities. The percentage rises to between 60% and 70% when the fertilizer used to grow animal feed crops is included.

It’s clearly a big task to address an issue like this; in fact, the study’s results ultimately suggest that we need to overhaul our entire food systems if we want to stop exporting unhealthy air and environmental damage to the regions that can least afford it.

“In the short term, rectifying the persistent disparities in pollution distribution within mainland China’s food systems is challenging,” says Professor Kwan Mei-Po, Choh-Ming Li Professor of Geography and Resource Management and the co-leader of the study. “To ultimately resolve the problems, both the demand side and supply side need to be tackled, instead of just relying on producers or consumers alone. Mitigating food loss and waste and promoting a planetary-health diet on the demand side, coupled with structuring an efficient food supply chain, can substantially alleviate the environmental footprints of the food systems.” First, economic measures should be implemented to compensate the disproportionate health impacts borne by farmers and agricultural regions. Additionally, reducing pollutant emissions from the food systems requires immediate action.”

“Enhancing the efficiency of agricultural production through technologies such as mechanisation, automation and moderate-scale operations can not only boost yields but also curb pollutant emissions,” Professor Tai adds. ““In the long term, there needs to be a shift towards more intelligent planning of agricultural activities, with crop and cultivation and livestock raising more evenly distributed. If mainland China can get this right,” he says, “it could create a template for the global food system of the future.”