Shine a bright enough light on anything, and you’ll uncover something new. In the case of one ancient Peruvian civilisation, shining a particularly high-tech light on the mummified remains of bodies has given us entirely new insights into their culture – and opened up whole new possibilities for the study of ancient history.

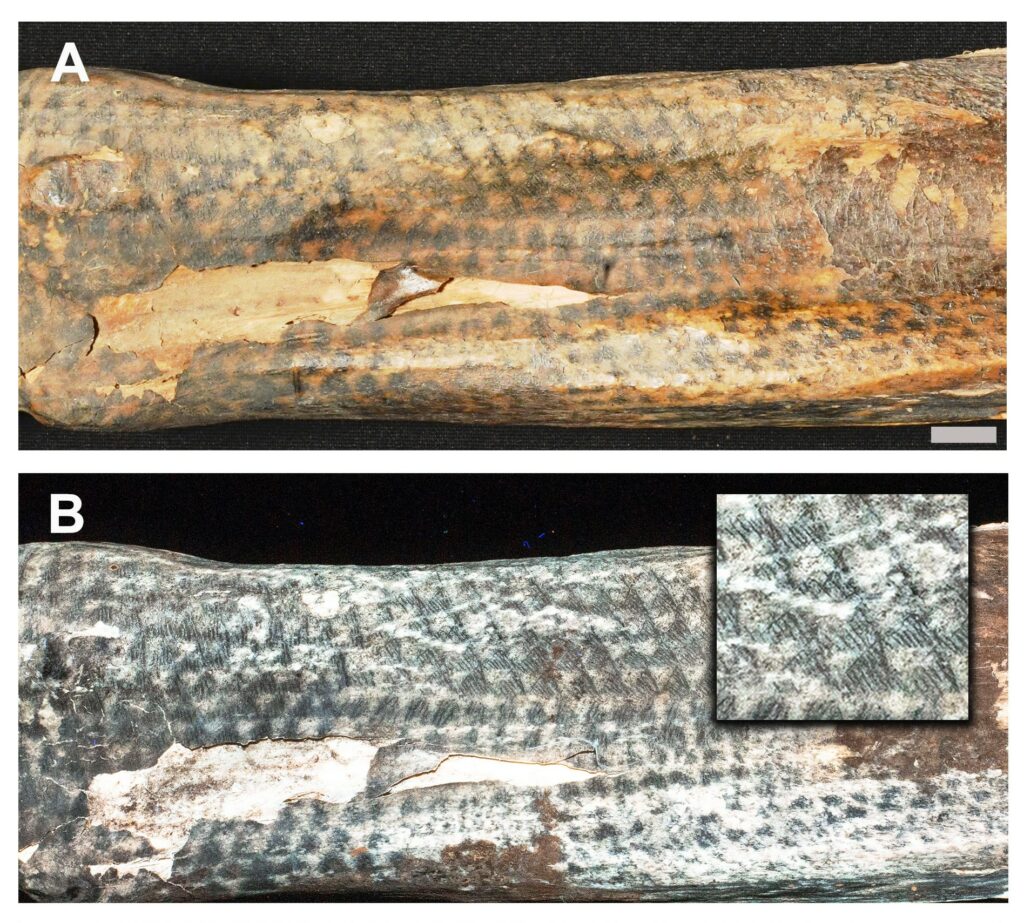

People have been tattooing their skin for at least 5,000 years, as remains found from the Alps to Egypt to South America demonstrate, and probably a lot longer. However, the passage of time often erases these cultural markers. There have been some pretty successful attempts to preserve bodies after death through embalming, as well as some that are accidentally preserved by dehydration – in both cases, we call them mummies – but the process of mummification darkens and toughens the skin, causing tattoos to fade and blur.

Laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF), a cutting-edge technology developed by a team led by Dr Michael Pittman, Assistant Professor in the School of Life Sciences at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), can do something about that. Originally designed to study dinosaur specimens, LSF uses lasers to generate high-contrast, fluorescent images. The technology took an unexpected turn when PhD student Judyta Bąk of Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland proposed using it on tattoos. This approach revealed intricate tattoos invisible to the naked eye, offering a stunning glimpse into the past.

The Chancay civilisation: a legacy etched in skin

The Chancay people thrived from about AD 900 to 1470 in the river valleys north of modern-day Lima, Peru – an area where the dry weather helps with the preservation of remains. Their culture, eventually absorbed into the more famous Inca civilisation, left behind a wealth of artefacts, including textiles and mummified remains. Among the approximately 100 sets of mummified remains studied, those that have been dated come from between AD 1222 and 1282, while others might date as far back as AD 900.

When the laser repeatedly scanned them in a dark room, the results were nothing short of magical: the skin glowed, while the tattooed areas remained dark, creating a stark contrast.

“Human skin should glow but anything on skin doesn’t glow as much – with tattoos, we think it’s because they’re made of materials like carbon that don’t fluoresce well,” says Dr Pittman. “This allows us to see intricate details that were previously invisible.”

Archaeological breakthroughs for over a century

The study revealed genuinely spectacular works of art, indicating a formidable level of artistic development. These intricate designs, visible on the arms, legs and torsos of some of the bodies, feature detailed geometric and zoomorphic patterns, many of which bear a striking resemblance to the Chancay’s famed textiles. With details as fine as 0.1-0.2 mm, these tattoos surpass the precision of modern tattoo needles, which typically measure 0.35 mm. In fact, one might argue that the art form has regressed over the past.

“We were absolutely astonished – basically speechless,” says Dr Pittman. “It surpassed our expectations. No one’s been able to do this in 100-plus years of archaeological study in the region.

“We wanted to demonstrate how LSF should be a new tool on the archaeologist’s tool belt. These are details we couldn’t capture using conventional photography or infrared imaging. When tattoos are heavily degraded, getting more information is crucial for interpreting their meaning.”

Tracing the stories behind the ink

The study suggests tattoos likely served as important cultural markers, possibly denoting status or spiritual significance. However, their exact meanings remain largely speculative for now.

“The meaning is the difficult part,” says Dr Pittman (who, for the record, doesn’t have any tattoos himself). “What we can say is that there’s some diversity in the tattoos. They’re predominantly geometric patterns like diagonals and diamonds, but some resemble animals. There are also differences in the time and effort invested in them. If more time was spent on a tattoo, it suggests the individual may have held greater importance – a hypothesis we can now test.”

The team now plans to apply the same technology to other ancient tattoos from around the world, including even older ones. But the potential of LSF goes well beyond that: having already been used on dinosaurs and mummies, the technology could illuminate a wide range of other historical and scientific mysteries.

Bringing the new technology to Antarctica?

Indeed, LSF is currently getting another workout in a dramatically new context: the frozen expanses of Antarctica. That’s because Dr Pittman has the honour of being one of the handful of Hong Kong scientists on board China’s icebreaker Xuelong 2, which is exploring the frigid continent.

“I wanted to try this, but being a palaeontologist, going to Antarctica was the remotest thing on my mind,” he says. “What I’m trying to do is bring a spatial dimension to data collection there. We can scan a large area of ice and gather information about how things vary across the landscape; for example, does the distribution of microbes change? These questions are now very difficult to answer; you’d need to sample many times.

“Lasers have all these different uses, and LSF is fertile ground for new ideas. We borrowed the technology from biology and applied it to palaeontology, so we think it’s only right to pay it forward.”