Smart devices are great. They’re the essential fuel of the modern world and the glue that holds smart cities together. They power everything from sensors in smart factories to intelligent home devices, as well as autonomous driving systems and drones.

That all sounds great, but there’s a serpent in this technological Eden. As the number of such systems increases, so does the amount of processing that gets done locally, within those so-called edge devices, ones that sit at the periphery of a network, rather than on cloud servers at its heart. And, as those edge devices get smarter, allowing them to perform those tasks, it dramatically increases the system’s vulnerability to hacking – especially in an era of AI and machine learning, when the computing power that can be brought to bear on hacking, cloning and reverse engineering such devices is formidable indeed.

To keep them secure, each device needs to be verifiably unique and incapable of being cloned, so that it can be reliably authenticated. A CUHK team, led by Dr Liu Yang, Dr Pei Jingfang and Professor Hu Guohua from the Department of Electronic Engineering, has come up with a way of making this possible.

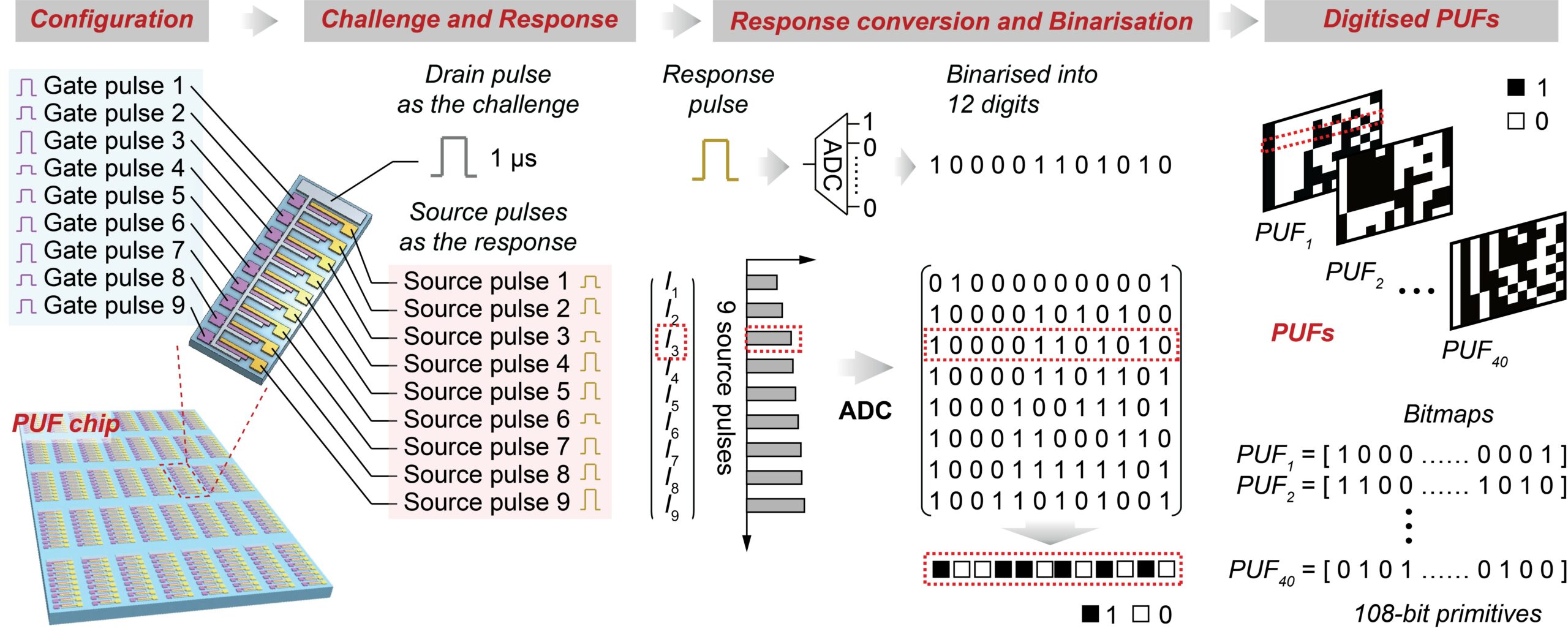

It’s based on a technology known as physical unclonable functions (PUF), better known as a digital fingerprint. They’re unique specifically because they’re not based on randomly generated digital values but on good old-fashioned physical materials. In this case, those materials are carbon nanotubes. The way they’re produced means that every one is different from every other one – and that quality can be exploited, providing guaranteed-unique responses to digital queries, a form of unique identifiers that allow for very robust security.

“Imagine arranging a handful of microscopic spaghetti into a perfectly orderly pattern on a plate,” says Professor Hu. “That would be the challenge with processing carbon nanotubes. During the fabrication of our carbon nanotube memory devices, the carbon nanotube bundles have to be processed in solution and deposited as thin films. At a microscopic level, the carbon nanotubes form random, entangled networks. We cannot precisely control the deposition of each individual carbon nanotube. This randomness is unique, unclonable in the individual memory devices fabricated and hence can be harnessed for PUF development.”

While these uncontrollable hardware variations make the PUFs impossible to clone, the technology also provides an extra level of security, because they can also be programmed in numerous different ways – more than 1013 different configurations in principle, in fact, a record for PUFs. Moreover, they can be reconfigured on the fly, close to instantaneously.

“Conventional PUFs are fixed once they are manufactured, which can make them easier to attack over time,” says Professor Hu. “Unlike conventional PUFs, our PUFs can be easily preprogrammed into different states, where in each of the programmable states, the underlying uncontrollable physical variations ensure the unclonability, securing the hardware security. The PUFs can be easily programmed on-site on command by simple erase-and-write operations of the carbon nanotube memory states. This means, in practical PUF operations, the server can send reconfiguration instructions remotely and the PUFs can generate a fresh set of unclonable challenge-response pairs.”

Traditionally, PUFs are based on silicon, but unlike the carbon nanotubes, that material can’t be reconfigured, making it particularly vulnerable to modern forms of hacking attacks on edge devices. The team’s new technology, by contrast, is so good at resisting those attacks that even the most advanced form of AI-based hacking can only manage to attack them successfully between 50 and 60% overall – and, of course, any form of attack could muster a 50% success rate through sheer guesswork. In fact, to crack an 108-bit PUF using a brute-force attack would take an estimated 1016 years – that’s nearly a million times the age of the universe. So: not likely.

The new tech could potentially be used in all sorts of devices, says the professor. “The core attributes of unclonability, reconfigurability and scalability can potentially make our PUF technology a universal hardware security solution for various edge intelligent systems, such as self-driving vehicles, robotics, drones and the vast universe of IoT sensors and systems.”

They’ve already been tested using a model of a self-driving vehicular communication network based on a map of Central, Hong Kong. They passed with flying colours, offering fast authentication, low computational overhead and minimal latency.

The next stage, says Professor Hu, is to move the technology from being something created in a lab to something that can be manufactured on a mass scale. The most practical way to do this, he adds, is to partner with manufacturers in sectors like self-driving vehicles, robotics and IoT systems. The route to commercialisation is still a long and complex one, involving prototype development, reliability testing and trials with industry partners – but with a potential roadmap in place, the day when smart devices are genuinely hack-proof is getting closer than ever.